How I got closer to the Queen drummer’s gear

The internet’s a funny old thing, a double-edged sword at the best of times. One minute you can be finding all sorts of information about stuff you didn’t know existed, the next arguing with somebody on the other side of the world you have never met. The latter is something I steer clear of these days, aided by my shunning of all things Social Media, but the former can produce the most unexpected and fulfilling experiences and truly enrich your life in the on-line world.

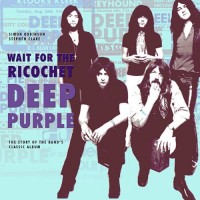

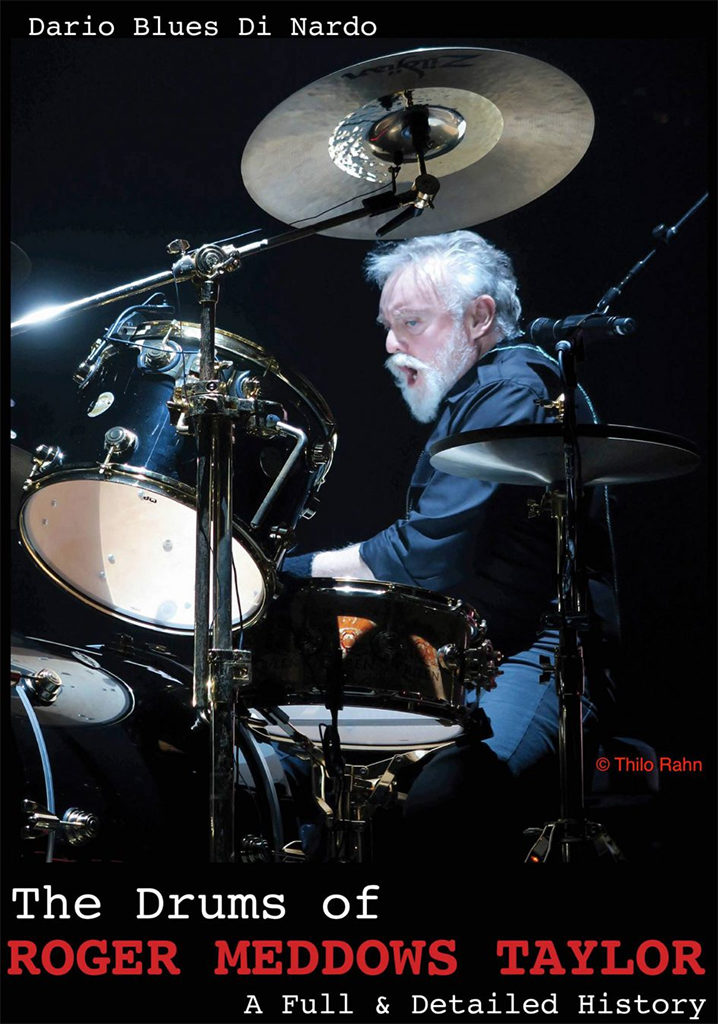

It was sometime in 2015 when I received an email via the contact page on this site, from an Italian calling himself Dario ‘Blues’ Di Nario. It turned out he had stumbled across my page on Roger Taylor where I describe his influence on me during my early teenage years. Dario was keen to communicate with me about all things Taylor because he had a very special project he needed to complete, one of a most highly classified nature. It turned out, he was in the middle of producing a book (the first and only book of its kind) detailing every drum set ever used by Taylor, from the pre-Queen days right up to the present day. With so little information in the public domain about Taylor’s gear, I knew this was going to be a tall order, but I was more than happy to assist in whatever way I could. It just so happened, the timing of Dario’s contact coincided with me commencing night school to learn Italian, so this was definitely a good omen in the alignment of the stars.

The first hurdle for Dario was putting his trust in me so I could see the current status of the project. Seeing as this book would be the first ever written on the subject and with so much information already collected, he had to be very careful about who he shared it with in case I, or anyone else turned out to be plagiarists with designs on making their own book! I had no such intentions and eventually he shared with me what he had achieved, so far. What he sent to me, even in its rough format, I could never have envisaged, not in my wildest dreams…

First of all, the level of detail afforded to the descriptions of the drum set components was nothing short of microscopic. To gather this sort of information with so little of it freely available to draw from, must have been a monumental task and one I certainly would not have had the patience to undertake. As well as being a work of forensic research, this was a dedicated labour of love or as they say in Italy, “un lavorare d’amore”. Secondly, the research Dario had completed on the textual and photographic sides of the story was equally as painstaking in detail. It took me very little time to realise I was dealing with a perfectionist.

Although Dario had asked me not to show or share the book with anyone, I knew I could show it to my boss (Andy Dwyer) who had shared many other secrets with me from the high profile drum world and could be trusted implicitly not to let the cat from out of the bag (I’m sure there is an Italian idiom for that phrase!) Andy was as jaw-dropped as me at the level of detail involved and fully understood the absolute need to keep it confidential.

So where did I fit into all this? My knowledge of Taylor was based upon a brief period as a teenager when I received my first drum kit. Dario had already cultivated positive contacts within the worldwide Queen fan club network as well as Brian May, Roger’s long-time Drum tech, Chris ‘Crystal’ Taylor and eventually, the man himself; so what could I possibly bring to the table?

Although Dario speaks good English and can write enough to communicate extremely well with English speaking people, it would be a tall order for him to write the book’s text to the standard required for general publication. So having graciously put his trust in me not to publicise the project, he asked me to become his Latinesque-English-to-proper-English editor.

Learn a foreign language and improve your English!

Having become involved with this project during my first year learning Italian, it was interesting to discover the differences in the way sentences are constructed between the two languages. Anyone familiar with the Star Wars films will know how the character (Master) Yoda speaks, in jumbled sentences that somehow make sense once the brain has rearranged them. Well, this is a near identical scenario when thinking in English to construct sentences in Italian, which means the translation from Italian to English by an Italian, can often read as ‘Yoda speak’! So much of my work was putting Dario’s words into something more familiar for an English speaking audience. However, I felt strongly about keeping his interpretation as close to the passion he has about his subject matter, so it was important not to over Anglicise his words.

Due to my low-achieving Secondary Modern school education of the late 1970s, English grammar was never taught to students of my level in any great depth. The massive eye opener for me during this experience – whilst continuing to study Italian throughout the project – has been how much I have learned about the grammar in my own language. If you want to learn about English grammar, then learn a foreign language!

The finishing line (‘finire’: to finish)

Working sporadically with Dario via email for many months, involving a seemingly never-ending stream of new information, edits, photographs and copyright headaches, Dario finally got his work to print during the final quarter of 2017.

With a limited run of 1000 copies and all profits being donated to his chosen charities, Dario produced a book with the level of detail in the subject matter I have never seen in any similar publication of its type over the last 30+ years. If a book like this had been available in the 1980s, it would have been like gold dust to a fledgling drummer such as myself. Having idolised Roger Taylor at a pivotal point in my early development, this book would have provided answers to the mystique surrounding the equipment of a personal drumming idol, and the pinnacle of what I dreamed of becoming.

I was lucky enought to gain access to Roger Taylor’s Ludwig Black Beauty Snare Drum for a private viewing at the British Music Show in Liverpool. One of the first batch of Black Beautys to come out of the Ludwig factory in 1977, rare as Hen’s teeth.

The badge serial-number and as Bill Ludwig III told me, badges were picked out at random from a huge container when being applied at the factory, so trying to date B/O badged drums is prety inconclusive in the absence of interior shell date-stamps.

However, we know the date of this drum, thanks to the engraving. Who is ‘PD’? I don’t know, perhaps somebody out there does?

Unveiling, the Italian way (‘svelare’: to unveil)

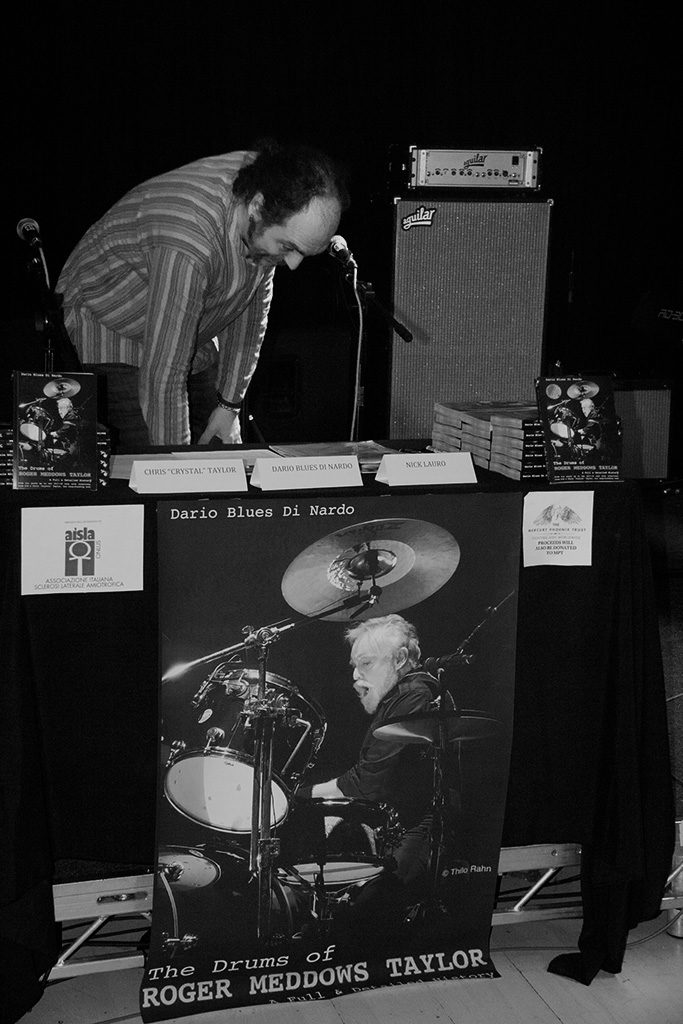

Having already proved his exceptional determination, ability to jump research hurdles, attention to detail, passion for his work and an unbreakable tenacity, Dario was no less impressive when organising the launch of his book. Somehow, he had managed to secure the ‘Roger Taylor Zildjian Studio’ at the Academy of Contemporary Music (ACM) in Guildford, for 24 January 2018. He was hoping Roger would turn up for the launch, but this was always going to be an extremely long shot. However, he did manage to get Taylor’s tech (Crystal) to attend (and speak) which was a nice gesture of support.

I was also invited speak about my involvement with the book, so I used my early morning train journey from Liverpool to London to write some guiding notes for when the spotlight was on me.

Having manoeuvred myself between the intense volume of humans at Euston and Waterloo stations, it was an almost surreal experience travelling on the near-deserted train to Guildford on a damp afternoon in January. However, my input into Dario’s project had been real enough, securing me the necessary worthiness to be in Surrey for the purposes of public speaking.

Meeting Dario and his wife for the first time was typical of my experiences with most Italians – one of warmth, passion and exuberance. Although we were meeting as strangers, I felt immediately comfortable in their presence, even daring to try out my raw Italian skills. Dario’s speed with conversational English was something I could only dream of with my Italian, as I listened to him easily multitasking between the two tongues. After ‘breaking the ice’, we quickly got to work with the preparations for the presentation, which involved Dario commanding the ‘Director’s chair’ with the same fiery, Italian passion that had propelled him throughout the project.

The cosy ‘Roger Taylor Zildjian Studio’ was decorated with some Taylor paraphernalia and there was a small stage at the bottom end with a PA. As I helped Dario and his wife unpack the books, I noticed three professional looking name cards set out on a table on the stage, printed with the names of Dario, Chris ‘Crystal’ Taylor and myself.

Dario directing!

View of the ‘Roger Taylor Zildjian Studio’ from the stage.

Yeah, that’s my name-place up there, unusually at the front of the stage, instead of at the back…

An ominous feeling of stage fright consumed me as I worried about exactly whom I would be speaking my train-scribbled words to…

When people began to arrive, I noticed many were Italians, had they really travelled all this way for a book launch? I wondered. The seating began to fill up and we waited for Crystal Taylor to arrive, being fashionably ‘Rock’n’Roll’ late. Somebody had set up a video camera and my nerve meter went up a notch at the thought of being captured speaking to an audience, rather than my usual stage persona of talking loud on a drum kit and saying nil-by-mouth.

Dario kicked off the proceedings (in excellent spoken English) before handing over to me, finally passing the microphone to Crystal to recount some of the more ‘family friendly’ Queen-on-the-road stories. And with that, it was all over, bar some book selling and signing by the author. As I had two-and-a-half hours to kill before my train back to Waterloo at 19:30, I realised there was a fantastic opportunity to spend some time with my Italian brethren.

Doing it like the Italians do (‘fare’: to do)

Whether by design or otherwise, there happens to be a Wetherspoons immediately next door to the ACM in Guildford, a spacious two-floor affair with a pleasant atmosphere. Due to spending a great deal of my life in bars and pubs behind a drum-set, I have very little experience of the Wetherspoons chain as they don’t seem to have live music as a rule. Apart from the large number of Italians with Dario, it was only myself, Crystal and the drum-tutor from the ACM representing the English – and even then it was vague, as both myself and Crystal have an Italian parent and the drum-tutor was a Scotsman!

The Italians beckoned me over to their table, giving me a chair and clearly welcoming me as a stranger to what was their party (or ‘festa’ as they say in Italy). Despite my paternal heritage, I have only been to Italy twice as a tourist to witness Italians socialising after dark. To sit with Italians in a social situation is entirely different to watching and wondering from afar. They do things a lot differently to my home country, I can confirm, and very much to my liking.

There are many beers available in the UK which are not readily available in Italy, and this was something the Italian men wished to experience. However, the attitude towards the alcohol was refreshingly restrained, preferring to enjoy the flavour of their beverages, rather than use them as a means to becoming shit-faced-drunk.

Another noticeable cultural difference was their propensity to order food (lots of it) and have it on the table to share. In Italy, this is known as ‘stuzzichini’ (which literally translates as ‘to pick at’) and the more familiar Spanish equivalent we know as, ‘Tapas’. The Mediterranean culture seems to have a rule that alcohol should never be taken without eating, so wine and food are enjoyed with the warm nights, vibrant conversation and laughter. A far cry from the average ‘Brits on the piss!’ night out, which usually ends with some/all of vomit, violence, regrettable sexual encounters, memory loss and hangovers.

Maybe I’m being a bit too harsh on my own country’s drinking habits, but we do seem to have cultivated an unfortunate reputation for drinking to excess, compared to other countries. Or maybe it’s the years of personal exposure doing gigs in the UK’s pub/club venues which has cultivated my negative viewpoint. Either way, I believe we have a lot of work to do as a nation to change our reputation in the world as binge-drinkers.

It ain’t big and it ain’t clever.

There is no pressure to drink in the Italian social experience, there is no competition to find out who can drink the most and stay standing and there doesn’t seem to be a focus on alcohol as the single motivator for ‘having a good time’. I noticed the same cultural altitude during a recent visit to Spain, where I spent a week living in a location with very few British tourists.

I can’t deny that I probably wanted to see these other cultures as having a more mature attitude towards alcohol than the country I was born in, and I dare say alcohol abuse exists in other European/Mediterranean locations. However, I stand firm with my experiences in Italy and Spain, which have offered me evidence enough to convince me that the excessive consumption of alcohol is not a priority within social occasions in the same way it is in the UK.

The brief couple of hours with my Italian Fratelli passed all too quickly and I found myself embracing my new friends with hugs, before taking myself off to the cold platform at Guildford station. As I clutched the still-warm cheese & tomato Panini Dario had bought me (I hadn’t been able to share the meat-based snacks they had ordered) it occurred to me even in a foreign country, the Italians had extended their hospitality so I didn’t feel left out.

Sitting on the train back to Liverpool, I reflected on what had been quite a bizarre day during which I found myself being rapidly blown through a whirlwind of activity, driven by the intense passion generated by an Italian’s dedication to his drumming icon.

Unlike Dario, I have never had the luck to meet Roger Taylor and it is an event I still dream of happening. To be part of this project has certainly been a door-opener in terms of my own personal development, confirming what I suspected the Italian social experience would be and reminding me there are still wonderful connections to be made via the internet, despite the sea of toxicity and division dominating the platform today.

I am pleased to have played a small part in Dario’s book, ‘The Drums of Roger Meadows Taylor’ and urge Queen/Taylor fans to buy it, not only because nothing else like it exists, but also because profits from sales go to charities close to Dario’s very generous heart.

To many British readers, this review is going to be controversial for which I make no apology. However, I must stress that despite how uncomfortable this might be for some, I am only ‘the messenger’ for a story that has surprised me, as much as it may shock and offended others.

To many British readers, this review is going to be controversial for which I make no apology. However, I must stress that despite how uncomfortable this might be for some, I am only ‘the messenger’ for a story that has surprised me, as much as it may shock and offended others.